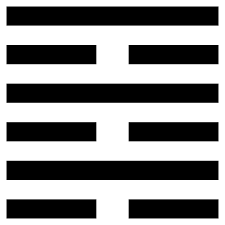

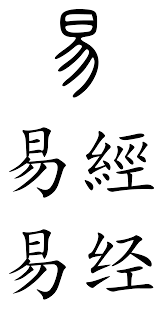

From 1974 to 1978, I studied at the Ontario College of Art and was enrolled in the Experimental Art program at the college. During this time, because of my other musical interests, I took experimental music classes with Udo Kasemets. By the time I met him, Udo was well established as one of Toronto’s pre-eminent avant-garde composers and his compositional tool of choice was the I Ching, the Chinese Book of Changes. I soon became Udo’s assistant for his regular concerts at OCA and the AGO and studied his approach to chance music, as best I could understand it.

EMBRACING THE MUSIC OF CHANCE

Udo’s principal compositional and organizational approach at the time was to organise a series of concurrent sound events (either pre-recorded or to be performed), something like a concert, and to create a map or plan for the performance(s) using the I-Ching. Sometimes these directions would be set ahead of the “concert/performance/event” and given to the performers and at other times, they would be executed by Udo himself in real time, somewhat like a conductor might direct/conduct a performance/concert in real time. By his own admission, Udo had been greatly influenced by John Cage, whom he had met in New York on several occasions, and while Cage continued to experiment with various forms of aleatory sound manipulation and control, Udo felt that the symbolic and referential dimension of the I-Ching provided ample room for all manner of musical and existential interpretation and meaning-making. It is, in fact, though Udo that I became interested in Oriental thought and philosophies and the numerous systems of Chance that existed through history and how they had been used, primarily in divination and other future-telling processes. The I-Ching led me to the Tarot which I studied even more extensively and used, in the broader context of the practice of “divination as a social practice in present times,” as the subject for my Master’s Thesis in Social and Political Thought at York University in the mid-1980s.

WHILE ELSEWHERE

At the same time, I was made aware of mainstream electronic music by several friends, including David Millar, a classmate of mine at OCA. David was a “true” early adopter of computer-generated music and he introduced me and others to the earliest sequencer software on the PC (created by then rock star Roger Powell). This music software was limited to generating sequences of only eight note at a time – which we would then string together to make our early sequencer parts. As the sages of olds, David M spent a summer at MIT to study computer music and came back, seemingly all the wiser for it. And at the same time, the first MIDI sequencer programmes for PC and Mac began to appear on the market, for those who could afford to experiment with the early iterations of DAWs.