The term experimental music covers of wide variety of musical compositions and listening experiences. At its most basic, experimental music is a form of music that seeks to move beyond the barriers of commonly accepted musical practices. Therefore, there can be experimental musical forms in any genre, from traditional classical music to jazz and beyond. The notion of musique experi-mentale became prominent in the mid 20th century when composers, such as Edgar Varèse, Pierre Schaeffer used certain specific sound production and manipulation techniques such as tape-recording manipulations and electro-acoustic sound generation to create and perform their compositions.

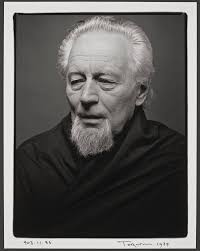

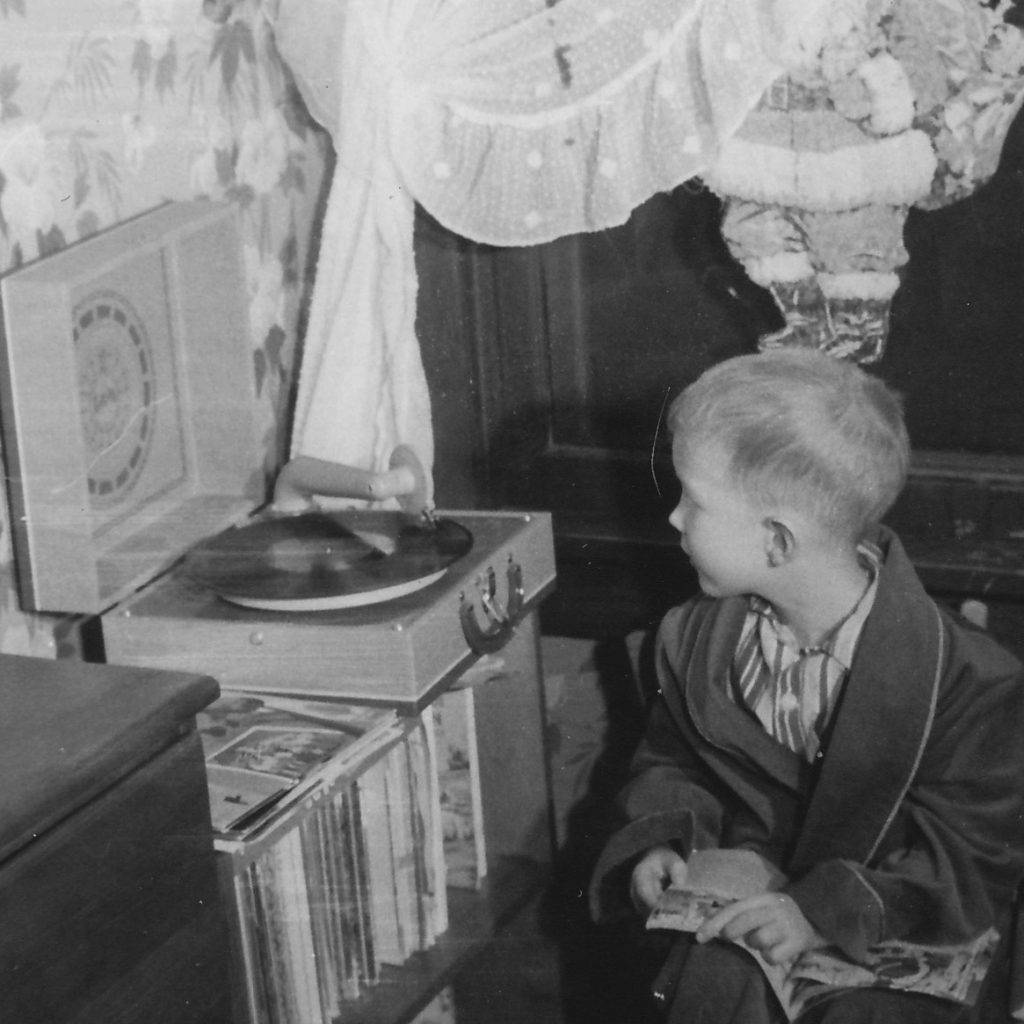

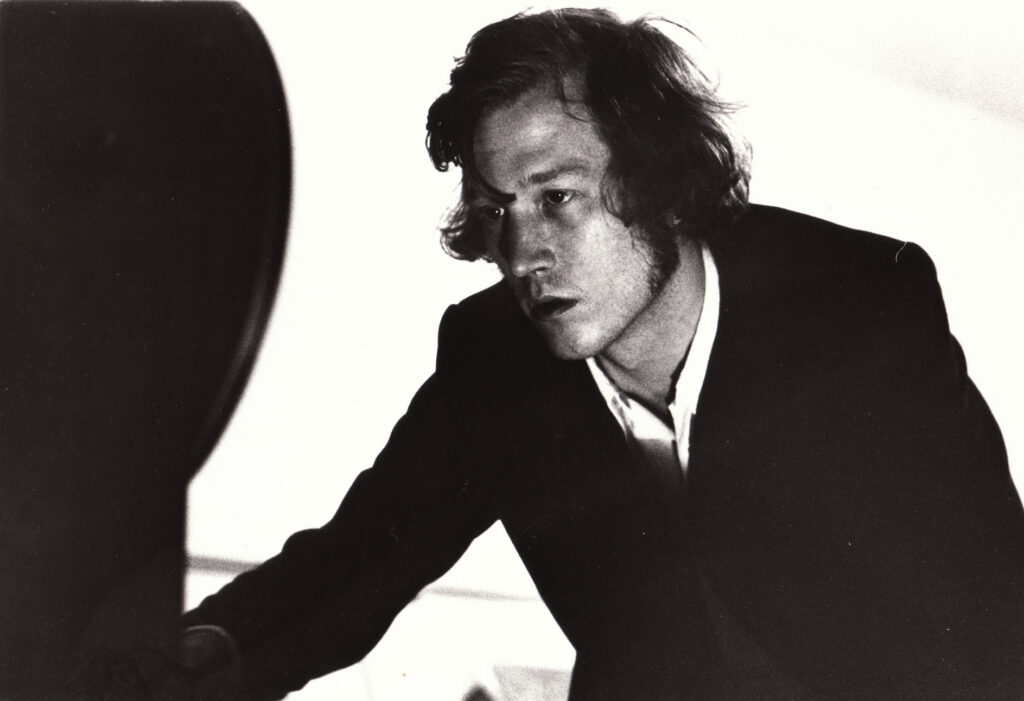

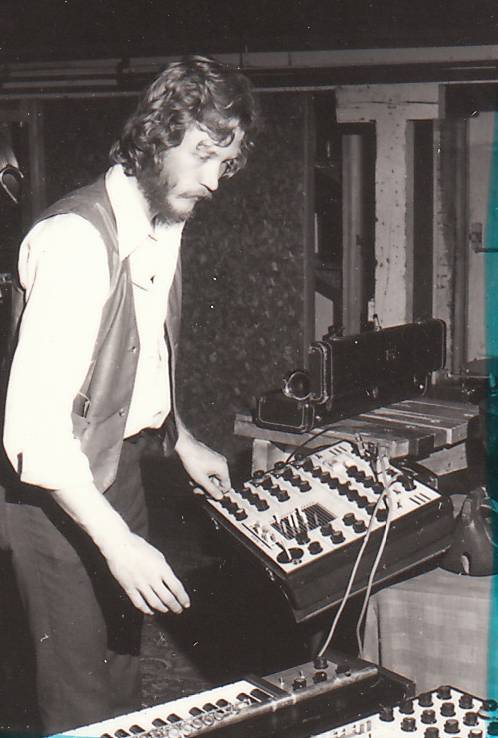

From 1974 to 1978, I studied at the Ontario College of Art and was enrolled in the Experimental Art program at the college. During this time, because of my other musical interests, I took experimental music classes with a composer by the name of Udo Kasemets. By the time I met him, Udo was well established as one of Toronto’s pre-eminent avant-garde composers and his compositional tool of choice was the I Ching, the Chinese Book of Changes. I soon became Udo’s assistant for his regular concerts at OCA and the AGO and studied his approach to chance music, as best I could understand it.

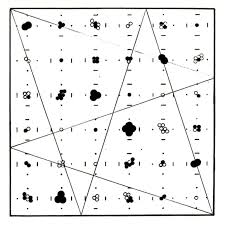

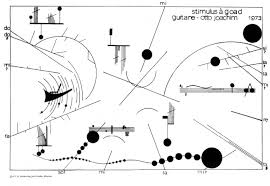

Udo’s principal compositional and organizational approach at the time was to organise a series of concurrent sound events (either pre-recorded or to be performed), something like a concert, and to create a map or plan for the performance(s) using the I-Ching. Sometimes these directions would be set ahead of the “concert/performance/event” and given to the performers and at other times, they would be executed by Udo himself in real time, somewhat like a conductor might direct/conduct a performance/concert in real time. By his own admission, Udo had been greatly influenced by John Cage, whom he had met in New York on several occasions, and while Cage continued to experiment with various forms of aleatory sound manipulation and control, Udo felt that the symbolic and referential dimension of the I-Ching provided ample room for all manner of musical and existential interpretation and meaning-making. It is, in fact, though Udo that I became interested in Oriental thought and philosophies and the numerous systems of Chance that existed through history and how they had been used, primarily in divination and other future-telling processes. The I-Ching led me to the Tarot which I studied even more extensively and used, in the broader context of the practice of “divination as a social practice in present times,” as the subject for my Master’s Thesis in Social and Political Thought at York University in the mid-1980s.

I was deeply inspired and transformed by Udo’s work and general approach to the world and I carry his influence with me to this day, as do many of his other students and colleagues.

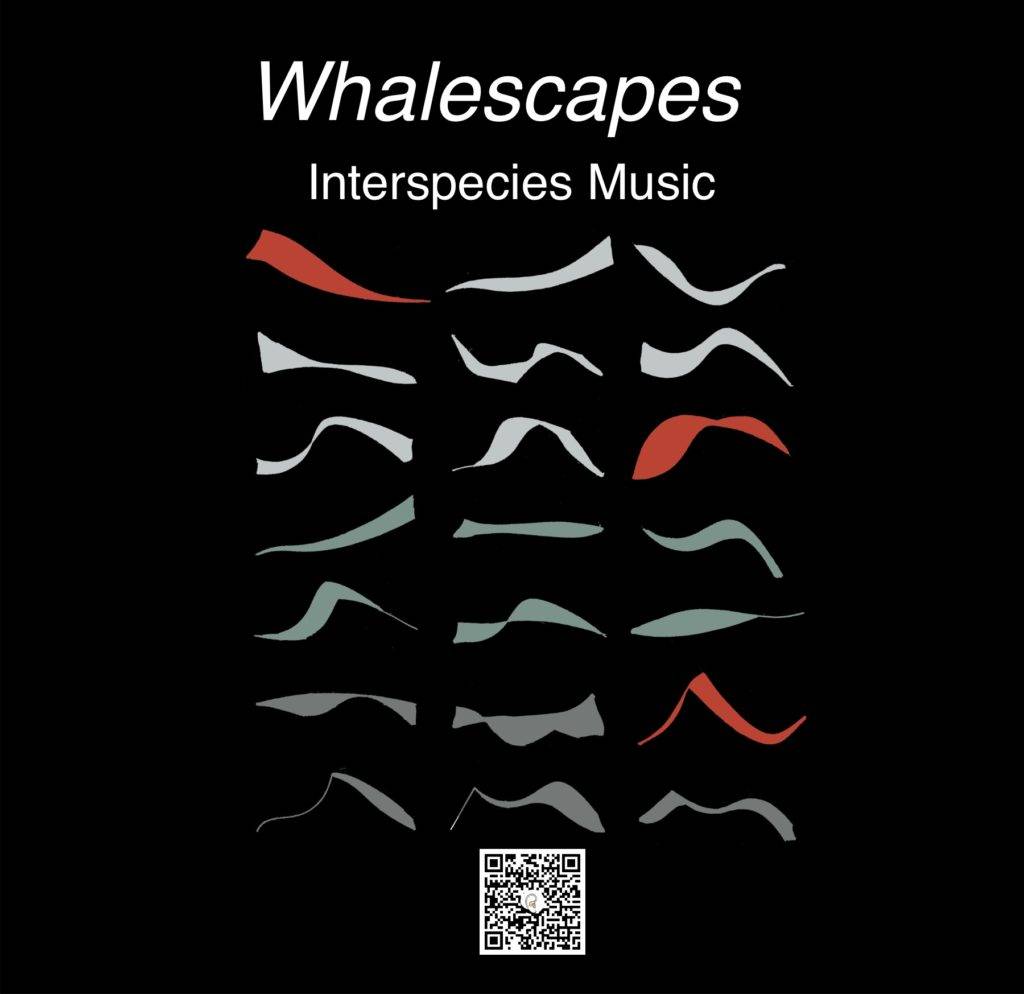

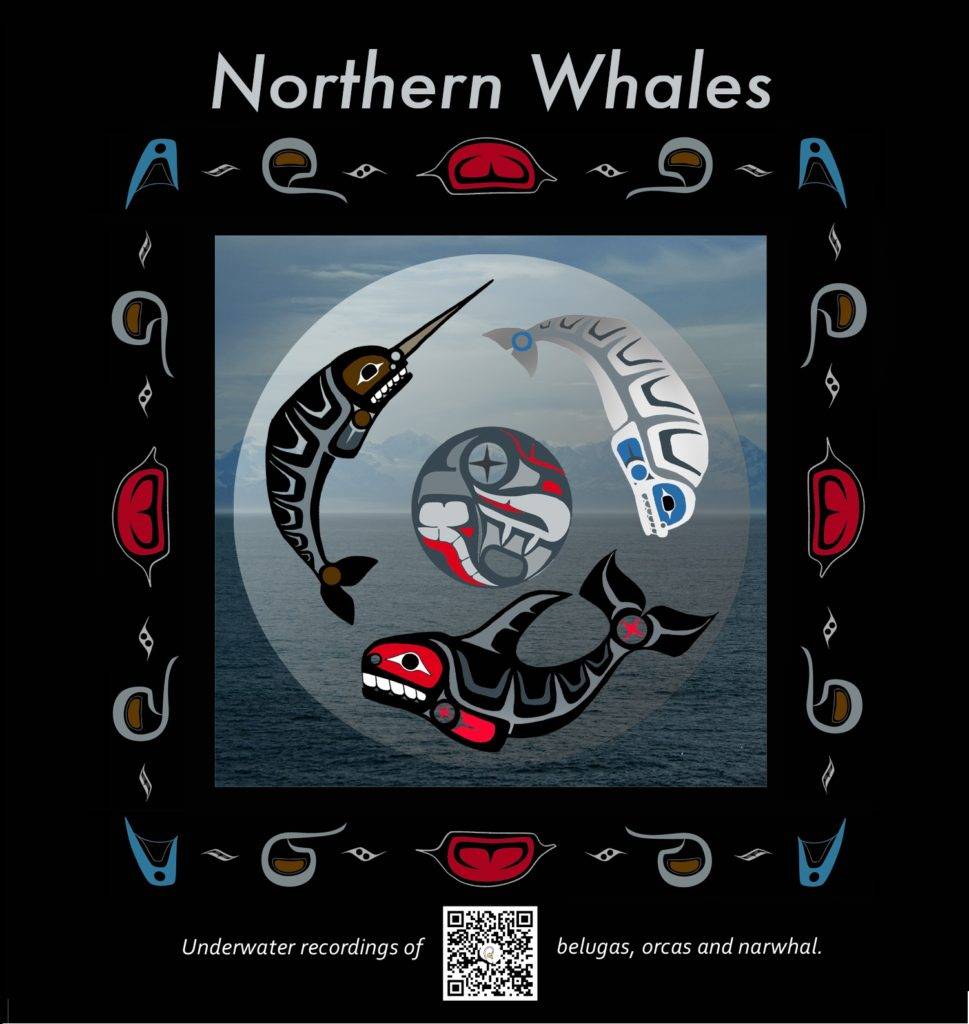

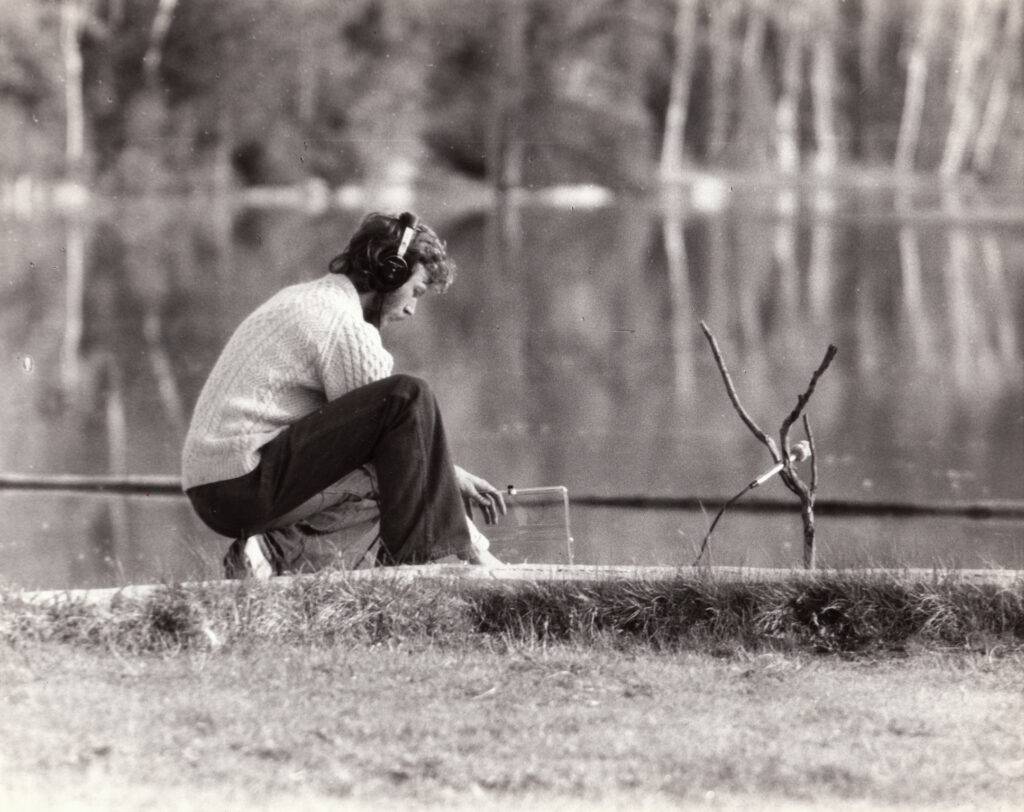

The study of Chance systems and other aspects of randomness and aleatory musical occurrences had a deeply liberating influence on my early music-making and opened up a variety of great musical experience, such as Interspecies Music (Whalescapes 1978), brain-wave music (Bird Waves 1978), improvisational electronic collaboration with clarinetist Robert Stevenson (Piece for 4 Solo Clarinets & Synthesizer 1980) and the re-imagining of TS Elliot’s Wasteland 1980with a young folksinger by the name of Kelita Haverland who has gone on to become a lifeforce for good in her own right. During this period, I also composed a free-form soundscape (Metalways) for the Judy Jarvis Dance company in 1978.