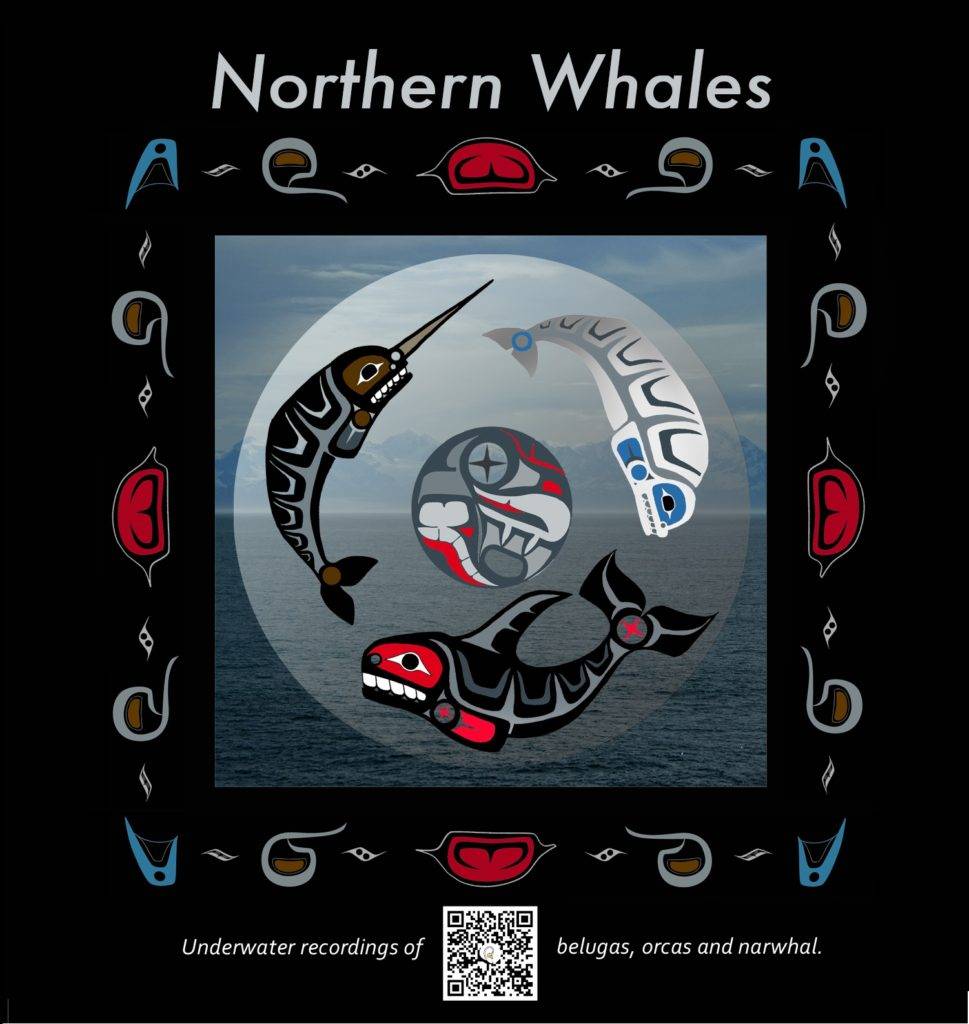

Underwater Recordings of Beluga, Narwhals and Orcas

The Recordings

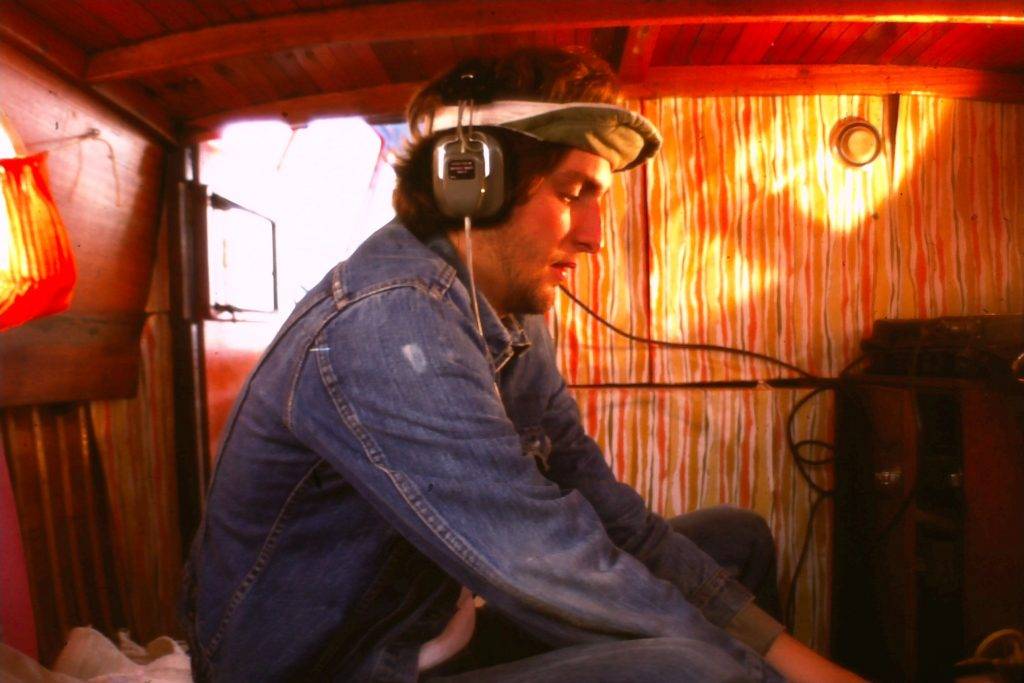

Certain phenomena are always present during underwater recordings. The wind and the waves create surface noise; the microphone cable itself transmits the vibrations of underwater currents to the microphone, submerged several meters under the surface and the boat, on which the recording devices are located, also can produce sounds that are heard underwater. In the high seas, long encounters with whales are rare, due in part to their natural reluctance to engage humans and because they are more preoccupied with their daily needs and survival.

In the recording under the ice, in Alaska, it is often impossible to identify the whales and other marine creatures who are several hundred meters away and invisible under the ice. The origin of the sound is also difficult to establish since the underwater communications of whales cover such a wide frequency range, from subsonic waves to 160,000 Hz, a problem compounded by the fact that water transits sound energy at four times the speed of air. As well, the omni-directional nature of the microphones require that they be separated from each other by several hundred meters before the human ear can perceive the so-called stereo effect.

Finally, industrial and commercial noises can greatly affect underwater recordings. In the St-Lawrence, where there exists a constant maritime traffic, one often can hear approaching vessels long before they appear on the horizon.

The Whales

There a three species of whales on this recording. We have also included other underwater sounds, such as those produced by the beaded seal or krill, a dietary staple of marine mammals in the Artic.

The Belugas

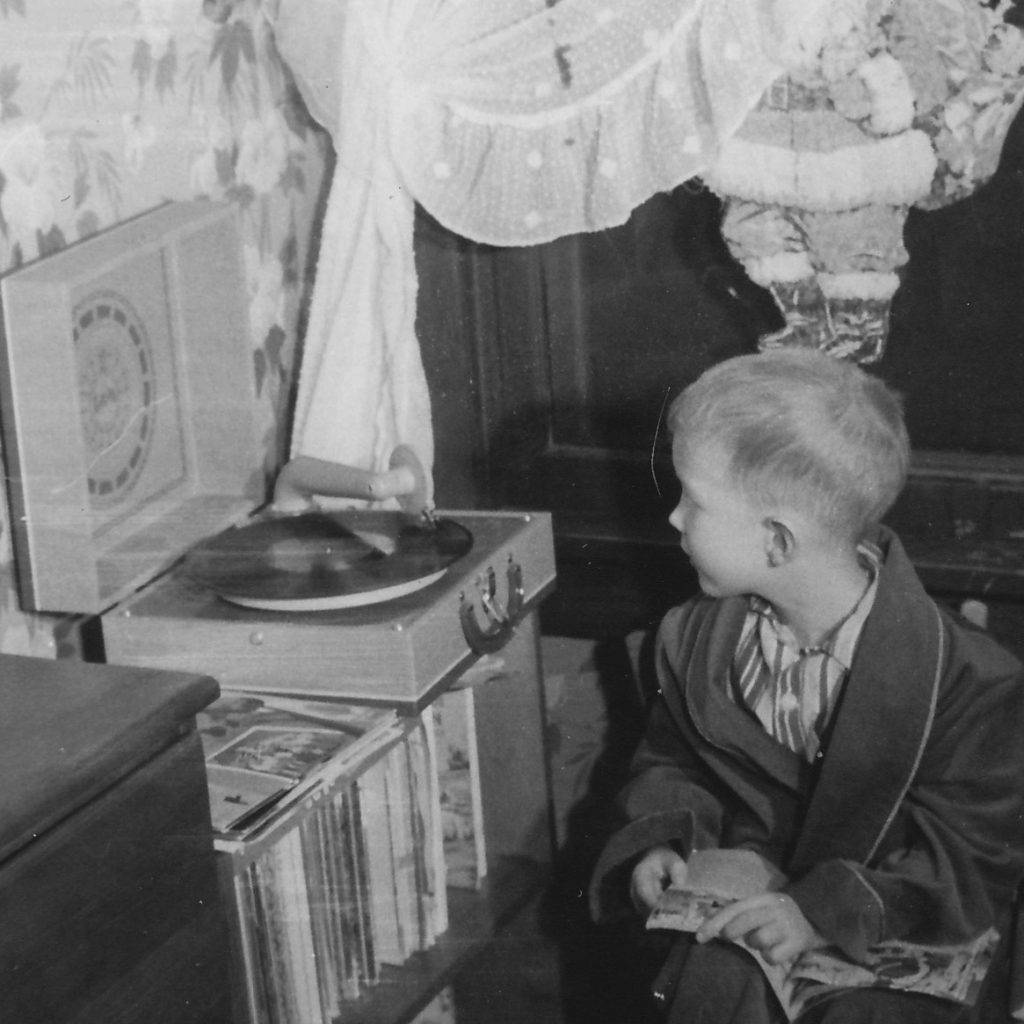

One of the fundamental ideas guiding Interspecies Music was that sound, and by extension, musical expression, had the ability to bridge the communicative gap between a number of species, particularly amongst mammals. At the time, there was intriguing research and some evidence that whales and other marine mammals possessed an intelligence at least as great as humans, and, using certain variables such as size of the animals brain and its neural complexity as well as the inherent difficulties of their environments, it was proposed that these creatures, and the great whales in particular, were a much more developed species than we were.

These small whales inhabit the cold waters of the artic and belong to the Monodontidae family. At maturity, the are about 15 feet long and their skin is white. It appears tat the belugas form pods several times a year, in winter, when access to the shallow waters of bays and reefs is impossible, and towards the end of spring when the calves are born. During the rest of the year, these whales form smaller pods to help in the search for food. Thee pods can be comprised of ten to several hundred belugas, depending on the overall local population. This mammal is rather shy and rarely seeks contact with humans. During our recording in the St-Lawrence River, a few belugas approached our boat as it drifted with the currents, as if to watch us, while the majority of the pod moved several kilometers away from us to continue feeding without concern. These behaviours on the part of the beluga seem to indicate a co-operative social structure and the willingness of group members to place themselves at risk for the benefit of the herd. We also witnessed other co-operative behaviour on the part of pod members when they form a line during the hunt in order to force a school of fish onto a shallow reef where they take turn feeding while others keep the fish from escaping.

The Narwal

a founding member of Interspecies Music

Although they inhabit the same artic waters and belong to the same genus as the belugas, the habits of the narwals are less well known. Male narwhals have been hunted extensively fir their tusk, which is in fact, the left tooth which can grow in a spiral 3 to 4 feet long. It appears that Narwals travel in groups of six or more, always of the same sex. In the artic, these whales follow the formation of ices, moving into deeper waters as the estuaries freeze over and returning to these when they break up and melt. This habit has been long used by fishermen to predict the arrival of winter aand also in the organization of the hunt. Adult Narwals reach lengths of 4 to 6 feet and their skins are entirely spotted. The back is dark brown while the belly is lighter, almost white.

The Orca

These dolphins are well known to visitors in various aquariums around the world because of their intelligence and the exciting shows for which they are trained.

In the wild, Orcas are immediately recognizable because of their dorsal fins and the white markings behind the eyes on each side of the head. This mammal is the undisputed master of the oceans. It appears that orcas mate for life and that they live in pods of six or more members, under the guidance of the elder male. A mature orca can measure up to 10 meters and their dorsal fin extend some 2 meters or more. The female of the species is smaller in size and their dorsal fin is curved. Orcas are the only dolphins who eat other warm-blooded mammals and is the fierce enemy of seals and smaller whales such as the beluga or the narwal. Orcas are also know to form packs in order to hunt larger whales, like the bowhead whale and right whales, specifically seeking out the young and the wounded and isolating them from the pack for easier prey. Orcas can be found in the warm and cld waters of the world, particularly along coastlines.

Playing to the Whales

We began be listening closely to the sounds produced by Humpback whales, particularly those recorded by Roger Payne off the coast of Hawaii and released in 1970. These songs were then methodically transcribed, using a visual notation system in order to better understand the order and sequence of various moments in the songs. It was also proposed at the time that the songs of the Humpback whales were analogous to the long epic narratives of the oral tradition, a retailing of past events and occurrences which were appended on a yearly basis the include the new occurrences experienced by the whales during the long migration from the Arctic to the Pacific.

Over time, we were encouraged to play sounds to whales and to elicit reactions from them that we, in turn, responded to.

The history of an endangered species.

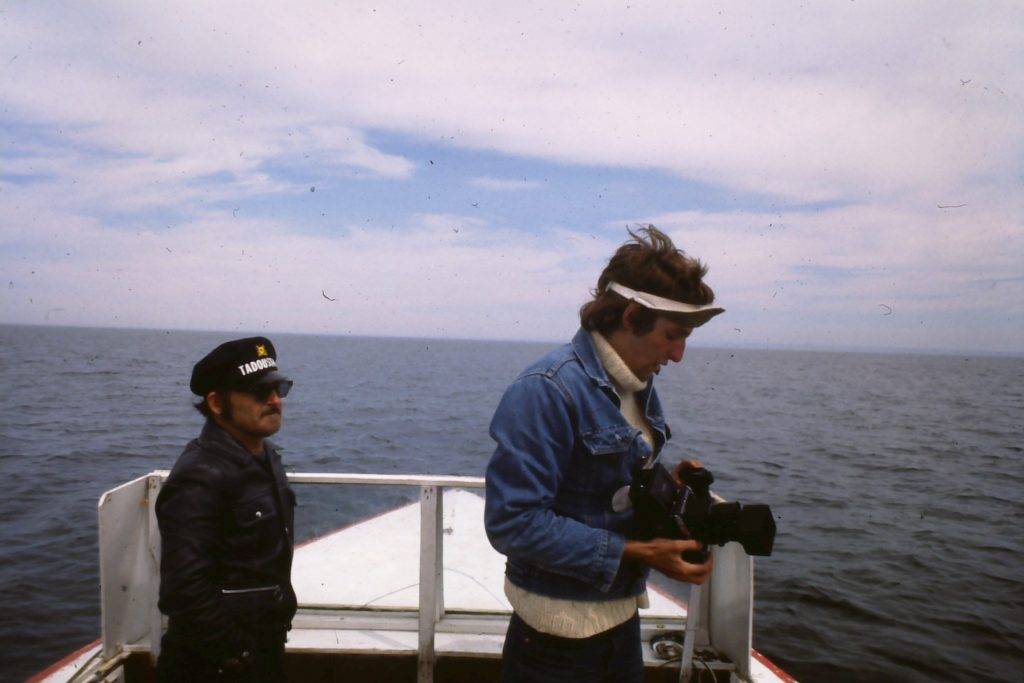

During our three summers in the Tadoussac area in the mid 1970s, we had the great fortune of meeting Henri Otis, a local guide with great in-depth knowledge of the indigenous marine wildlife, particularly the large whales who sojourned yearly in the Gulf as well as the belugas who lived year round in this region of the St-Lawrence. It was Mr. Otis who took us out to see the whales up close on numerous occasions, all the while regaling us with tales of his experiences and exploits over the years. He became our informant, to use a sociological terms, providing us with unique insight into local culture and practices. When he learned that some of us were musicians, he even introduced us to a number of North Shore performers and a recording of local folklore ensued aptly entitled, Sur la Côte Nord.

Mr. Otis was a wicked accordion player in his own right. Once, when we were in the middle of the river, we looked up to see an airliner on its way to Montréal, and Henri wondered aloud what flying might be like. I immediately invited him to visit me in Toronto and we arranged for him to stay with us. Unfortunately the Big Smoke was not for him, and within 2 days, he was overcome by homesickness and we arranged for an early flight home. To his knowledge, Henri was the only one from his town to have travelled to Toronto and he once told me, in passing, that his brother and he had once been to Québec City when they were young. The trip took them three days on foot and they so disliked the city of Québec that they stayed a few hours, ate and drank their fill, then turned back to return home, always on foot.

Henri Otis told us many stories about his encounters and dealing with the local whales, both as a hunter and a guide to others. Once, having discovered that the melted blubber from belugas produced a very high grade oil that worked exceedingly well in motors, his brother and him went to Québec City in the hopes of creating a business for themselves. Another time, he accompanied foreign hunters who wanted to kill a great whale. While they managed to harpoon it and blow up a dynamite charge attached to the harpoon, mortally wounding the Blue whale, it managed to escape them and was later found ashore several miles up river, left to decompose on the beach and causing an uproar with the local population.

Until the early 1970s, the belugas and other whales in the St-Lawrence estuary were thought to pose a significant threat to the local fish stock and therefore to directly impact the local fishing economy. Henri Otis told of the wholesale slaughter of belugas calving in la Baie du Soleil. at the mouth of the Saguenay by government sanctioned hunters using helicopters to track down the whales and shoot them, He recalled the base itself running red with the blood of the dead and wounded mammals. Eventually this practice was stopped when research revealed that the fish eaten by the whales were not the same as those harvested by the local fishermen. But by then, nearly irreparable damage had been done to the original herd and direct government action was required.

More on the Marine Parc in the St-Lawrence

parcmarin.qc.ca/get-to-know/

Northern Whales – the recordings

Belugas in the Arctic – Cut 1 (3:08) (Cut 2 (1:19)

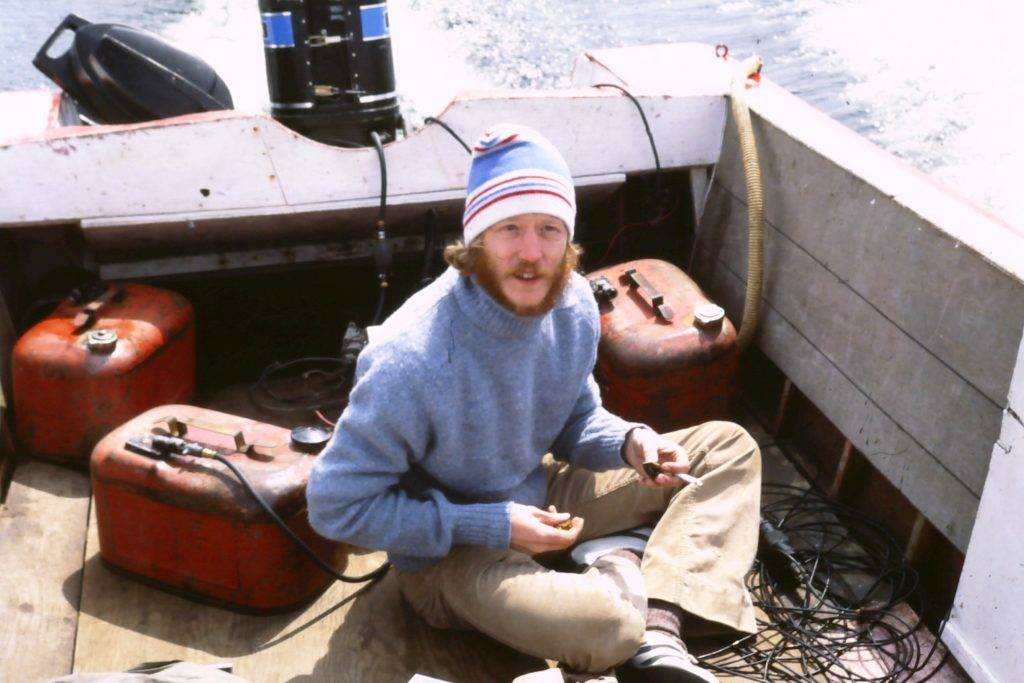

Belugas produce and extraordinary array of sounds and these recordings by Chester Beachell in Cape Lisburne Alaska on April 19, 1973, are very good examples of the whales communications. The microphones were submersed to a depth of about 15 meters under the ice.

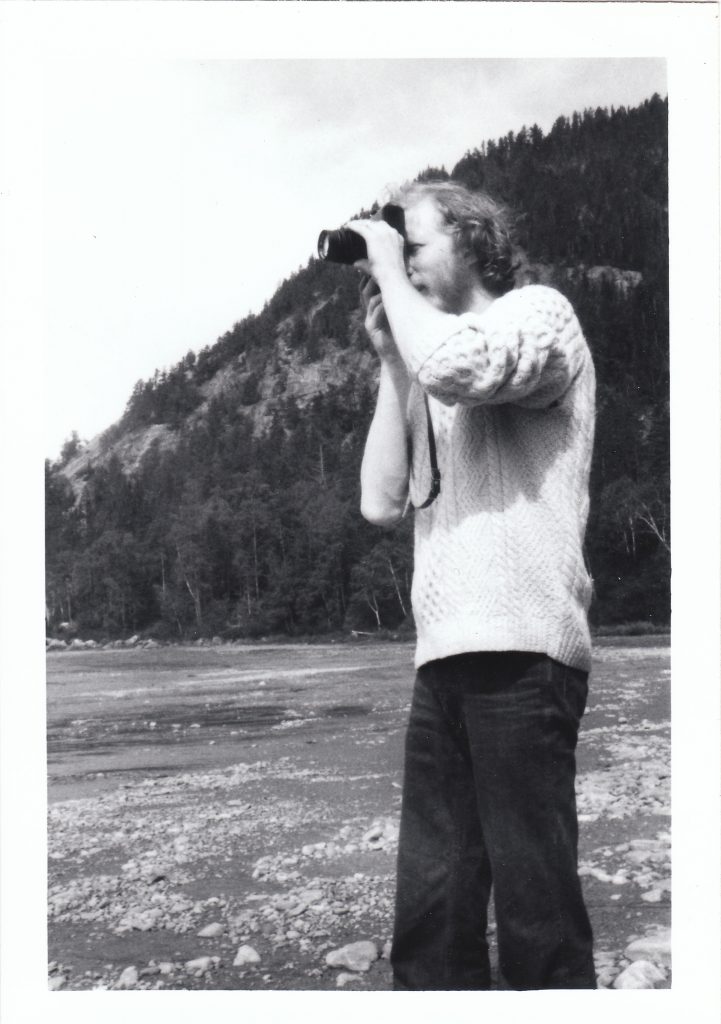

Belugas in the St-Lawrence During the summer of 1977, Pierre Ouellet recorded these belugas near Les Escoumins, on the North Shore of the St-Lawrence River. The group of whales was encountered on the high sea, about 10 kilometers from shore.

Cut 3 (2:17) These are primarily echolocation sounds produced by the beluga. During this recording, the drifting boat was surrounded by about twenty or thirty whales while one member of the group swam directly below us, at a depth of about 6 to 8 meters.

Cut 4 (5:18) A minke whale surfaces in the middle of a group of belugas whose reactions is swift and is intended to scare off the intruder. Another section of this recording can be found on the Interspecies recording entitled Whalescapes.

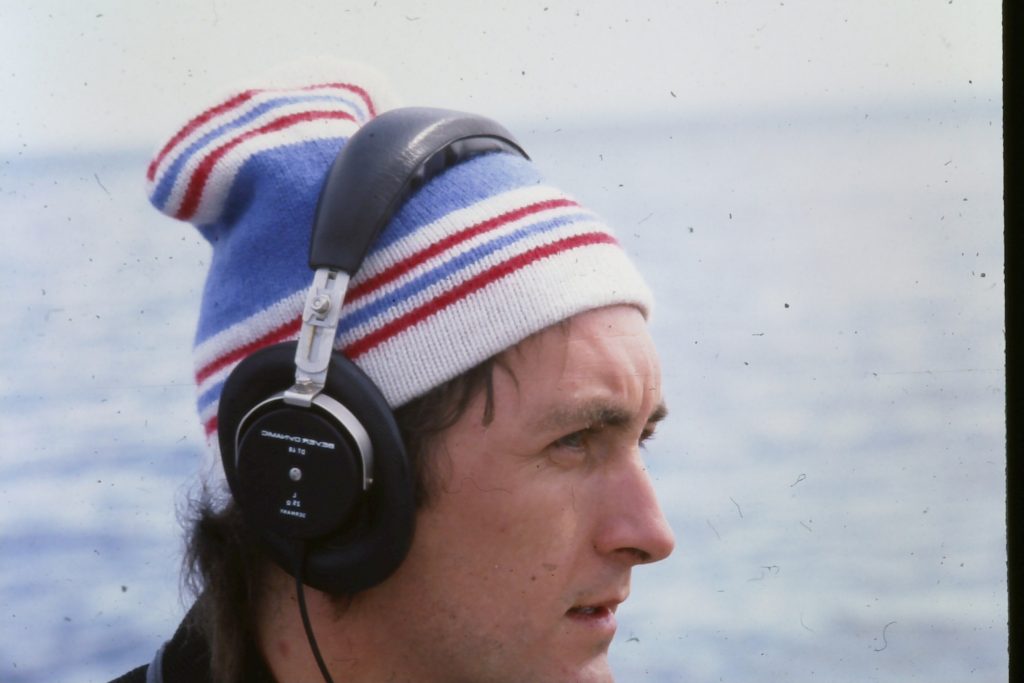

Orca Cut 5 (1:21) & Cut 6 (0:46)

recorded by Chester Beachell, off the coast of British Columbia.

Cut 7 (0:36)

The orca in captivity was recorded by Chester Beachell. Notice the difference from the recordings of the orca in wild on side A.

Narwhals in the Arctic Cut 8 (4:24)

In August 1975, Mr. John Ford received a grant from the Vancouver Aquarium to record Narwals. These whales were recorded in Koluktoo bay, at the tip of Baffin Island. On the day the expedition arrived at their base camp, around 6:00 am, a group of between 100 and 150 animals appeared in the bay. The microphone was placed about 30 meters from the shore, at a depth of about 20 meters.

Alaskan Krill Cut 9 (0:21)

recorded by Chester Beachell, under the ice in Alaska.

Bearded Seal Cut 10 (3:15) & Cut 11 (1:47)

These recordings by Chester Beachell in Cape Lisburne Alaska on April 19, 1973.

Stellar Seal Cut 12 (0:53)

These recordings by Chester Beachell in Cape Lisburne Alaska on April 19, 1973. In this later recording, belugas can be heard in the distance.

Orcas and Belugas

The following two pieces are sound collages of previously heard material as well as excerpts from other unreleased recordings.

Orca and Belugas – Soundscape I Cut 13 (9:35)

The orca is the natural enemy of belugas. In this recording, we hear the belugas response of the approach of a pod of orcas, as they seek the relative shelter of the shallow bays and costal reefs. A few of the older whales remain behind the herd to distract the Orcas as they approach.

Orca and Belugas – Soundscape II Cut 14 (6:50)

A few times a year, when the conditions are propitious, belugas gather by the hundreds, if not thousands, in shallow coastal estuaries and bays. Arial photography has been taken of such grouping where more than 100,000 animals were grouped together. In this piece we hear all manner of marine life, beluga, narwhals, bearded seals and so forth, carried on the thermal layers of the frigid waters.

Special Thanks and Acknowledgements

Special thanks to all who contributed to this project: Chester Beachell, John Ford, The Music Gallery Editions and Marvin Green, The exploration program for the Canada Council, Gerald Isles, Dennis Pike, Ammo Studios, Murray Newman and the Vancouver Public Aquarium, and finally, all the members of Interspecies Music.

Originally re-recorded at the Music Gallery and Ammo Studios, January 1979. Cover art by Arnold Sprogis, Sculptures by Steven Aikenhead, Art Direction by Francis Sanagan. Part of the research for this record was made possible by a travel grant from Paul Fleck, President of the Ontario College of Art.